On writing binary files in Stata/Mata

As a supplement to my most recent posts, I decided to put together a quick guide on writing and reading binary files. Stata has a great manual for this – however, I struggled to see how this works in Mata. I spent a good afternoon scouring Google, Stata Journals, and Statalist to no avail. Little did I know, I was looking in the wrong places and for the wrong commands. It wasn’t until I broke out my old Mata 12 Mata Reference guide that I realized the solutions lie not with fopen(), but with bufio() (and yes, bufio() is referenced in fopen() - always check your references)

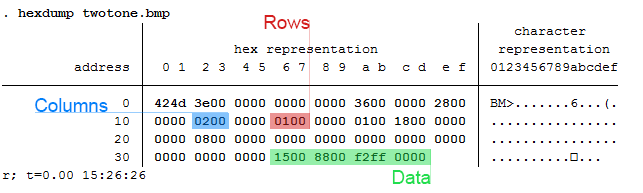

We start by making up a fake type of file called a wmm file. This file always begins with the hex representation ff00, which we know just means 255-0 in decimal or 11111111 00000000 in binary. The next 20 characters spell out “Will M Matsuoka File” followed by a single byte containing the byte order or 00000001 in binary. From there, the next four bytes contains the location of our data as we put a huge buffer of zeros before any meaningful data. It makes sense to skip all of these zeros if we know we don’t need to ever use them. After these zeros, we’ll store the value of pi and end the files with ffff. The file looks like this: Stata's File Command

tempname fh

file open `fh' using testfile.wmm, replace write binary

file write `fh' %1bu (255) %1bu (0)

file write `fh' %20s "Will M Matsuoka File"

file set `fh' byteorder 1

file write `fh' %1bu (1)

* offset 200

file write `fh' %4bu (200)

forvalues i = 1/200 {

file write `fh' %1bs (0)

}

file write `fh' %8z (c(pi))

file write `fh' %2bu (255) %2bu (255)

file close `fh'

The only thing I feel I need to note here is the binary option under file open. Other than that, take note that we’re setting the byteorder to 1. This is a good solution to writing binary files; however, since most of my functions are in Mata, we might as well figure out how to do this in Mata as well. Mata's File Command

If you didn’t know, Mata’s fopen() command is very similar to Stata’s file commands, with a few slight differences that we won't touch on here. Just know, it's pretty awesome and don't forget the mata: command!

mata:

fh = fopen("testfile-fwrite.wmm", "w")

fwrite(fh, char((255, 0)))

fwrite(fh, "Will M Matsuoka File")

// We know that the byte order must be 1

fwrite(fh, char(1))

fwrite(fh, char(0)+char(0)+char(0)+char(200))

fwrite(fh, char(0)*200)

fwrite(fh, char(64) + char(9) + char(33) + char(251) +

char(84) + char(68) + char(45) + char(24))

fwrite(fh, char((0,255))*2)

fclose(fh)

end

I personally like the aesthetic of this syntax; it’s clean, neat, and relatively simple. The only problem is its ability to handle bytes. In short, it doesn’t do it at all. We’d have to build some more functions in order to accomplish this task (especially when it comes to storing double floating points) which is why Mata also has a full suite of buffered I/O commands. It’s a little more complicated, but well worth it. After all, we cheated in converting pi to a double floating storage point by using what we wrote in the previous command. This is not a good practice. Mata's Buffered I/O Command

Let's get right to it

mata:

fh = fopen("testfile3-bufio.wmm", "w")

C = bufio()

bufbyteorder(C, 1)

fbufput(C, fh, "%1bu", (255, 0))

fbufput(C, fh, "%20s", "Will M Matsuoka File")

// We know that the byte order must be 1

fbufput(C, fh, "%1bu", bufbyteorder(C))

fbufput(C, fh, "%4bu", 200)

fbufput(C, fh, "%1bu", J(1, 200, 0))

fbufput(C, fh, "%8z", pi())

fbufput(C, fh, "%2bu", (255, 255))

fclose(fh)

end

The one distinction here is the use of the bufio() function. It creates a column vector containing the information of the byte order and Stata’s version, but allows us to use a range of binary formats available to use in Stata’s file write commands. Reading the Files Back

Now that we’ve written three files, which (in theory) should be identical, let’s create a Mata function that reads the contents stored in these files. Note: it should return the value of pi in all three cases. As it turns out, they all do.

mata:

void read_wmm(string scalar filename)

{

fh = fopen(filename, "r")

C = bufio()

fbufget(C, fh, "%1bu", 2)

if (fbufget(C, fh, "%20s")!="Will M Matsuoka File") {

errprintf("Not a proper wmm file")

fclose(fh)

exit(610)

}

bufbyteorder(C, fbufget(C, fh, "%1bu"))

offset = fbufget(C, fh, "%4bu")

fseek(fh, offset, 0)

fbufget(C, fh, "%8z")

fclose(fh)

}

read_wmm("testfile-fwrite.wmm")

read_wmm("testfile.wmm")

read_wmm("testfile3-bufio.wmm")

end

And there you have it, a bunch of different ways to do the same thing. While I enjoy using Mata’s file handling commands for its simplicity, it does get a little cumbersome when writing integers longer than 1 byte at a time. Time to start making your own secret file formats and mining data from others.

1 Comment

You’re being tracked – in the world we live in today, almost everything you do has some sort of digital trace. I recently went to True North Tavern in North Park (San Diego) to mourn yet another 49er defeat – and to my surprise, they had a bouncer at the door checking IDs. I’ll admit, I am very lax in giving out my ID to anyone who asks for it, but on this occasion I did hesitate to provide identification a little as I saw a big black machine right by the door. Luckily, I made it through after a quick glance but as it turns out, a few friends were not so lucky. Besides visually checking ID’s the bouncers sometimes scan driver’s licenses into these black machines, which stores the patron’s driver’s license information including the photo! Today, we will explore why this is a very bad practice as we transition to talking about Exif data.

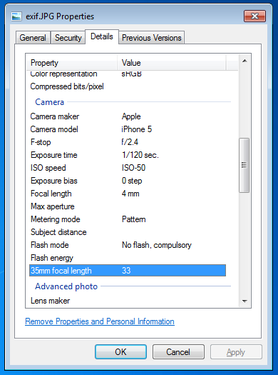

Exif, or exchangeable image file format, is a way to store information on your images or audio file. If you have an iPhone, you will probably notice that you can actually view your images on a map, and it shows you where and when you took the picture. This is really neat, especially if you’re a photo editor and need to match light or camera settings in Photoshop without having access to the physical camera. However, this is also incredibly dangerous. Here is a quick look at the properties of a photo I took with my iPhone 5.

You can see everything, including the exact location of where I took the picture. Now, I’m sure this is not all that shocking, but it can be a little nerve wracking when you post pictures online knowing that someone can easily trace back where you were with a click of a button. Luckily, many social media websites such as Facebook and Twitter are aware of this and will strip your picture’s Exif data for you.

Exif data are stored in the header of your picture. What the heck does that mean? Every picture contains a header, and most new cameras and cell phones will actually write this data in the header. Your computer then reads this information and is able to tell your location, camera settings, and time stamps of the photo. One section actually contains all of the Exif tags – it’s really just a collection of information. In order to read this information, we have to read in the picture file which is a series of zeros and ones. Yup, we’re using Mata’s bufio() functions to read in all of this information. Bufio() allows us to write not only string characters, but also binary integers into files without using Stata’s file command. I will bore you with the details in a subsequent post, but for now, I’d like to introduce my program – exiflatlon – which strips JPG, TIF, and WAV file formats of latitude and longitude information. It can be used in two ways:

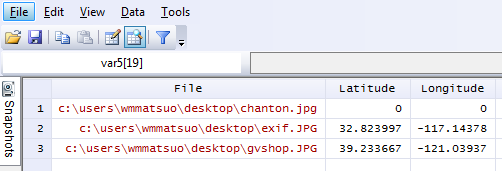

Let’s try out the directory specification.

exiflatlon, dir("C:\users\wmmatsuo\desktop")

In the event there is no exif information, exiflaton will provide you with a warning and will replace those latitude values and longitude values with zeros in the resulting dataset. It only takes milliseconds to rip the locations off each photo – and this is valuable information, especially if you don’t want the wrong type of people (or really anyone) tracking you. While I only use Stata for good, there are likely people who use it for bad purposes. Only joking, Stata users are never malicious, but there are plenty of other programmers who are and who have more efficient tools at their disposal for such (and maybe creepier) purposes. In today’s age, we need to be careful about safeguarding our data because there are no moral boundaries when it comes to taking data. Companies love information, and will not hesitate to steal this information. After all, hiding the fact that “by entering this premise, you consent to us taking all your information from your ID” is in no way consent when it’s not clearly stated. I’m looking at you, True North Tavern...

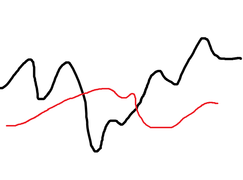

Have you ever been burdened with making up data? Of course not, you say! How dare you charge me with such accusations! Well first, calm down. Sometimes it’s okay to “make up” data. For instance, for testing purposes: perhaps you have an idea of the approximate shape of the data you’ll be feeding into your program, but some lazy programmer isn’t providing you with the necessary steps to proceed. You could create a sinusoidal function to create an approximate representation, but who really has the time for that. The solution lies with a 3rd grader’s doodle.

Balderdash! But really, it’s much easier to draw out the shape of your data that to input it cell by cell or create some function that’s going to be scrapped in the end anyway. Even better, perhaps someone put this graph in a presentation, but is refusing to share their base data. No problem for us. For this tutorial, we’re going to need to download GIMP, a free graphics editing software program that’s similar to Photoshop, but also drives me crazy because it has completely different hotkeys.

Take this image and open it in GIMP. Then make sure to save it as an HTML webpage. By selecting this option, GIMP converts every pixel to a cell in an HTML table, allowing for us to parse this information out ourselves. Remove HTML tags and only keep relevant information: each <td> tag should have a background color which is the hexadecimal RGB color of the cell. Recall that <td> tags indicate cell data whereas <tr> tags indicate a new row. Since each line contains a new bit of information, we don’t really care about the td tags. In fact, tag the <tr> tags (gen trtag = regexm(lower(v1), “<tr”), and take the running sum of that variable (replace trtag = sum(trtag)). This way, we have a corresponding row to each point of data. Create a running count variable by each row - this will give us column positions. Create a variable that’s equal to our column position gen black = run_count if y == "000000" gen red = run_count if y == "ed1c24"

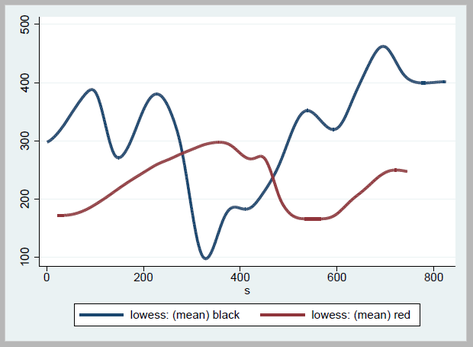

Finally, collapse your black and red variables by your column variable: collapse black red, by(colpos) fast To make everything look nicer, I used the lowess command to smooth out my lines, but you don't have to if you're looking to get extremely accurate data. lowess black s, bwidth(.08) gen(bsmooth) lowess red s, bwidth(.08) gen(rsmooth)

* s represents our row count variable (trtag)

Finally resulting in: line *smooth s, lwidth(thick thick)

which gives us the following output in Stata:

PLEASE NOTE: Stealing graphs and making up data are bad practices. I wouldn't actually do this in the professional setting. This post merely serves to show how this process may be done. I recently celebrated my Birthday, which is an occasion where I can’t help but reminisce about the past or stop over-thinking about the future. This also (closely) marks my two-year work anniversary, which precedes my two years of experience at the Energy Commission, two years of Graduate School, and that one year at UC Davis where I first learned about this great software called STATA. Little did I know back then that it was a very big deal to spell Stata correctly. In looking back at my experience at work, it’s easy to forget what I have done, and even easier to forget what I do on a day-to-day basis. In order to help jog my memory, I wrote a crawler that scrapes all of our directories and all my personal files for any do-files I have written in these past two years. I image the Twelve Days of Christmas tune when going over this list… but I really shouldn’t. 8 million characters typed 2 million words a-written 200,000 lines of codes 1,700 do-files 1,250 SQL statements 830 graphs 230 times invoking Mata 100 programs All influenced by 3 coworkers that greatly shaped my code. To create these numbers, I made good use of dir(), along with the fileread and filewrite functions. For a more detailed list of what I like to start my lines with, check out the attachment below!

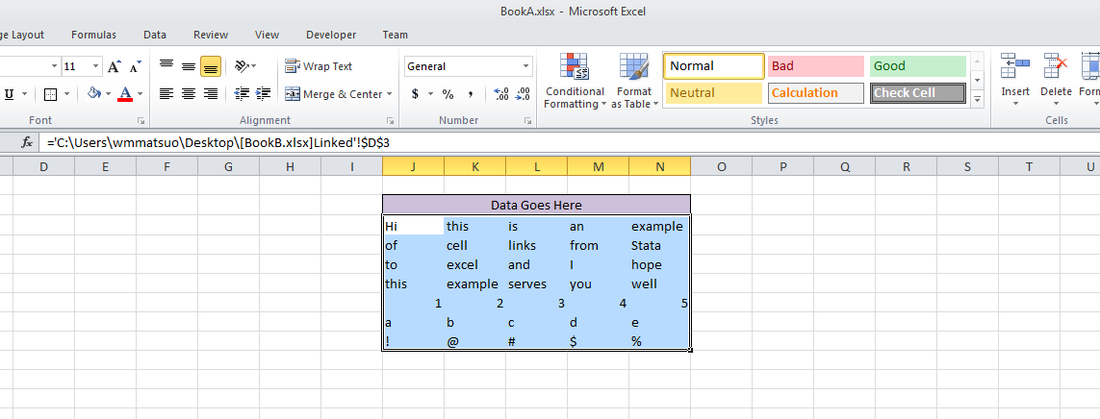

Coercion. It’s the topic of the day, and a short topic at that. Coercion is the leading driver for Excel usage for most Stata users. Workbook linkage is usually a pain – the practice of linking one cell from a workbook to a different cell in another workbook – and can turn a relatively simple task into a nightmare usually ending the job with a headache and a stiff drink.

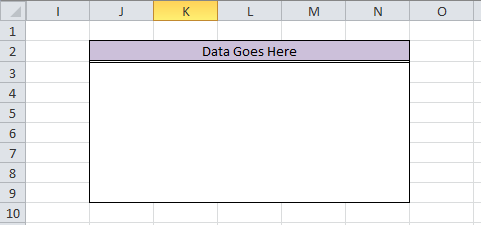

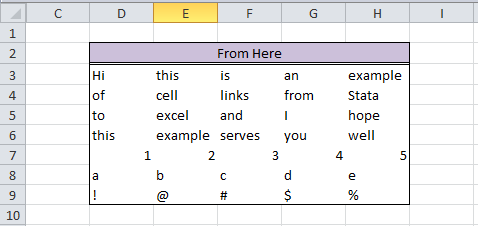

However, with a few simple Mata commands, the crisscross of equal signs, dollar signs, and formulas can turn a repetitive task into a few simple copy-and-paste commands. There is also less room for error. For fun, we'll do this entire thing in Mata. First, we need to decide how many observations/variables we need. Let’s look at our current workbook and target workbook.

So we need 5 columns and 7 rows, with columns from D to H and rows from 3 to 9 in our BookB set. Write it:

mata:

st_addobs(7)

st_addvar("str255", "v" :+ strofreal(1..5))

Starting with a blank dataset, add seven observations. From there, we create 5 variables (v1 v2 v3 v4 v5) that are all of type str255. This is a placeholder value for long equations. The second part of this command “v” :+ strofreal(1..5) is my favorite part about Mata. The colon operator (:+) is an element-wise operator that is super helpful. No more Matrix conformability errors (well maybe a few). It creates the matrix:

("v1", "v2", "v3", "v4", "v5")

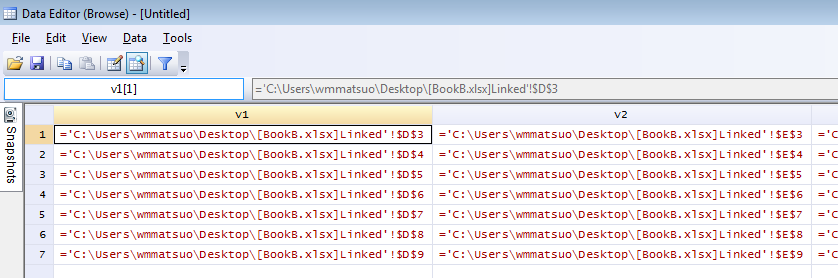

without much work and allows for any number of variables! Sidenote – changing (1..5) to (1..500000) took about 3 seconds to create 500,000 v#’s. Next, let’s set up our workbook name: bookname = "'C:\Users\wmmatsuo\Desktop\[BookB.xlsx]Linked'!" Specify the location of the workbook with the file name in square brackets and enclose the sheet name in apostrophes. End that expression with an exclamation point! Since we know we want D through H, and cells 3-9, we can write the following: cols = numtobase26(4..8) rows = strofreal(3::9) numtobase26() turns 4 through 8 into D through H. For more information see my previous post on its inverse. The rows variable is a column vector containing values 3 through 9. Now it’s time to build our expression: expr = "=" :+ bookname :+ "$" :+ J(7, 1, cols) :+ "$" :+ rows We put an equals sign in front of everything so that Excel will know we’re calling an equation. Follow that with the workbook name. If you didn’t know, dollar signs in excel will lock your formulas so they don’t move when you copy formulas from one cell to another. We’ll put those in as well. The next part, J(7, 1, cols), takes our column letters and essentially repeats it seven rows down. Thanks to the colon operator, we just have to add another dollar sign to all elements of the matrix and our row numbers. Since the new cols matrix contains seven rows, and our row vector contains seven rows, it knows to repeat the row values for all columns. Let’s just put that matrix back into Stata and compress our variables.

st_sstore(., ("v" :+ strofreal(1..5)), expr)

stata("compress")

end

And voilà, we have a set of equations ready to copy into Excel. One quick tip: set your copy preferences so that when you copy the formulas, you won’t also copy variable names by going to edit->preferences->data editor-> uncheck “Include variable names on copy to clipboard”. Now just copy the equations directly from your Stata browse window into Excel, and enjoy those sweet results! In other news, this post built upon the putexcel linking discoveries found over at belenchavez.com - who recently had her Fitbit stolen! Follow her journey to get it back on her website or on Twitter - hopefully she'll be able to coerce the thief into returning the device.

This post is one of my white whales – the problem that has eluded me for far too long and drove me to the edge of insanity. I’m talking about writing binary. Now, let me be clear when I say that I am far from a computer scientist: I don’t think in base 16, I don’t dream in assembly code, I don’t limit my outcomes to zeros and ones. I do, however, digest material before writing about it, seek creative and efficient solutions to problems, and do my best to share this information with others (that’s where you come in).

First, let’s create a fake dataset with help from Nick Cox’s egenmore ssc command:

set obs 300

forvalues i = 1/200 {

gen x`i' = round(runiform()*50*_n)

}

gen id = _n

reshape long x, i(id) j(vars)

egen count = xtile(x), nq(30)

keep id vars count

Today we will be making a bitmap of a map for Fitbit activities by writing bits of binned colors in a binary file. Alliteration aside, this post pulls from various sources and is intended to cover a great deal of topics that might be foreign to the average Stata user – in other words, hold on tight! It’s going to be a bumpy bitmap ride as we cover three major topics: (1) Color Theory, (2) Bitmap Structures, and (3) Writing Binary Files using Stata. Color Theory

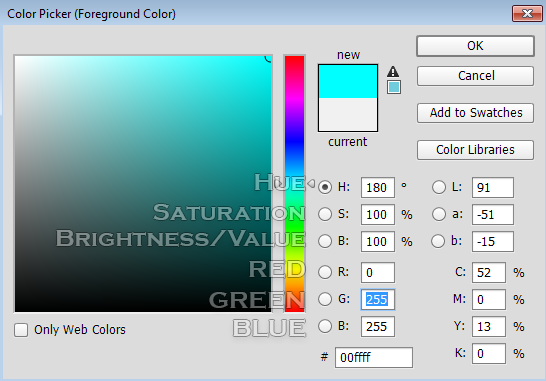

In creating gradients, it was recommended to me to use a Hue, Saturation, Value (HSV) linear interpolation rather than the Red, Green, Blue (RGB) interpolation because it looks more “natural.” I will not argue this point, as I know nothing about it. For me, I know that if I play with the sliders in Photoshop, it automatically changes the numbers and I never have to think about what it’s actually doing in the conversion. In order to convert from RGB to HSV and vice versa, I used the equations provided here – to learn about what’s going on, Wikipedia has a great article on the HSV cones!

|

|||||||||||||

| bitmap.do | |

| File Size: | 4 kb |

| File Type: | do |

Author

Will Matsuoka is the creator of W=M/Stata - he likes creativity and simplicity, taking pictures of food, competition, and anything that can be analyzed.

For more information about this site, check out the teaser above!

Archives

July 2016

June 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

Categories

All

3ds Max

Adobe

API

Base16

Base2

Base64

Binary

Bitmap

Color

Crawldir

Email

Encryption

Excel

Exif

File

Fileread

Filewrite

Fitbit

Formulas

Gcmap

GIMP

GIS

Google

History

JavaScript

Location

Maps

Mata

Music

NFL

Numtobase26

Parsing

Pictures

Plugins

Privacy

Putexcel

Summary

Taylor Swift

Twitter

Vbscript

Work

Xlsx

XML

RSS Feed

RSS Feed