Why Care Block:

Yo yo, what’s up my Stata-ites! DJ Control+D is in the house because today we’re talking about making music with Stata. There’s a big trend in today’s age involving visualizations, but truth be told, visualizations are so last season. You’ve always been able to see your data, yet have you ever wanted to hear your data? “That’s absurd, I don’t need that.”

Yeah, you’re probably right... but today, this post is for the slacker: from the undergraduate struggling through their Stata homework, to the professional who’s bored with the day-to-day grind, our new command composer is there to brighten up your day and aid with your ever evolving procrastination techniques. What is composer? It’s a way to create music. How is that music generated? You write a string of notes that get converted to the midi file format. Why did we do this? I’m still asking myself that same question while introspectively reevaluating my life. Truth be told, I love music. Not in the traditional sense, but in the very traditional sense – classical music and music theory has always been a passion of mine and this has been a passion project for a long time now. Composer makes music in two separate ways. You can write songs from the command line and from a dataset. The command line approach is faster and is especially meant for ad hoc procrastination. The dataset approach is a more methodical way of creating music and actually allows for multiple tracks and multiple instruments. Take our command line approach: composer "D, 384D, A, A, B, B, *2A, G, G, F#, F#, E, E, *.25r, *.25Db, 768D" using tt.mid, play replace We could have also written this first part as D, D, A, A, B, B, 768A, but it’s good to see the variations of this command. First we have notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Each note can be modified using a # (sharp) or a b (flat) which directly follows the note. A number before the note shows the duration of the note. The quarter note takes the value 384 (3*2^7). This way it can be halved up to seven times with 384 representing a quarter note, 192 representing an eight note, 96 a sixteenth note, and so on. Rather than specify a value, you may also multiply the note by a number to modify the value of the quarter note. Any number following your note denotes which octave or pitch your note will take. You may also change the instrument using a number or a named instrument available in the composer help file. For instance, say we wrote:

local n1 = "F#,A,E6,D6,E6,D6,A,D6"

local n2 = "E,A,E6,D6,E6,D6,A,D6"

local n3 = "F#,B,E6,D6,E6,D6,B,D6"

local n4 = "G,A,E6,D6,E6,D6,A,D6"

composer "`n1',`n1',`n2',`n2',`n3',`n3',`n4',`n4'" using ls.mid, play replace instrument("Pizzicato") bpm(240)

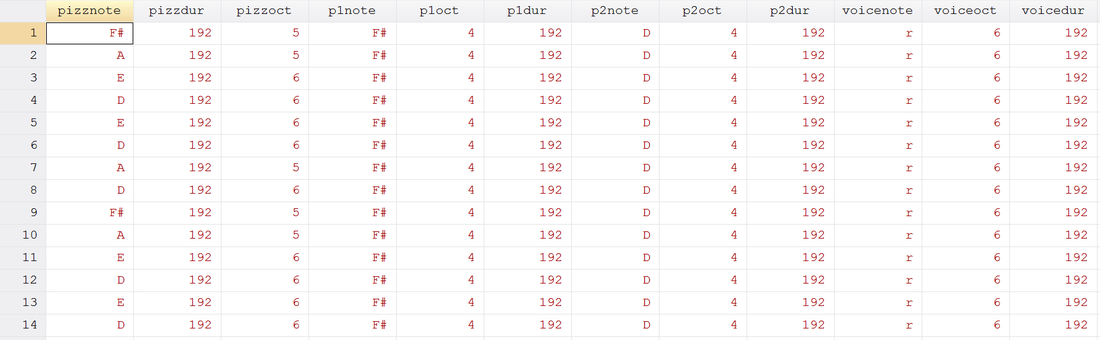

See if you can identify the song! Now take our data set approach. It’s just like the command line approach, except the command now takes sets of three variables: time duration, note, and octave. Notes can be played simultaneously by adding another track (three more variables). This way we can build chords and add volume to our masterpieces just like Beethoven. But unlike Beethoven, we’re not creating classical masterpieces, we’re recreating pop music. If you weren’t able to pinpoint the song before, here’s the dataset aided version of our previous track.

use http://www.wmatsuoka.com/uploads/2/1/4/6/21469478/ls.dta, clear composer pizzdur pizznote pizzoct p1dur p1note p1oct p2dur p2note p2oct voicedur voicenote voiceoct using ls.mid, play replace bpm(120) instrument(Pizzicato Pizzicato Pizzicato Voice) And there we have it, a fairly easy way to write music in Stata. Is this interesting? I hope so, especially if you’ve made it this far. I’m sure you’re wondering how useful this is though. Truth be told, this is probably one of the only things on this blog that I haven’t found a general use for but perhaps you can find some sort of practical application and share your thoughts. There will be one more post about music soon which deals with the actual analysis of music which will use composer. Until then, good luck and stay creative future Stata maestros!

25 Comments

Bitwise Operators (aka Bits, Bits, Bits Part II)

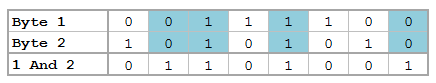

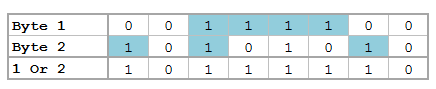

Did you know that Mata supports bitwise operators? Well, it actually doesn't – in the typical sense. But that won't stop us from making it work. You see, Mata can handle data extremely well, and with a little finesse, can be forced to do things it wasn't really made to do. Yes it's going to be slow, and yes it's probably not very useful to the average user, but let me try to convince you how great using Mata really is!

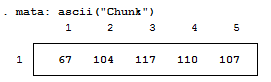

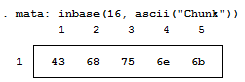

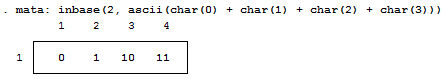

For those who don't know, Mata is a lower level language than Stata – many of Stata's complex functions are actually written in Mata because it's really quite fast. Mata mimics a lot of C's syntax, but also simplifies things so you don't feel like you have to explicitly declare everything. In previous posts we've exploited the power of the - inbase() - function and we will make ample use of that today. Say we have a text file containing the word "Chunk". While we see a word, the computer sees numbers which correspond to each letter – otherwise known as ASCII. Mata's - ascii() - function can help us find this representation:

This is a simple way of converting our text into numbers, but how about into bytes? Typically, bytes are displayed in base 16:

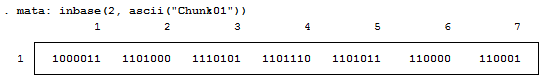

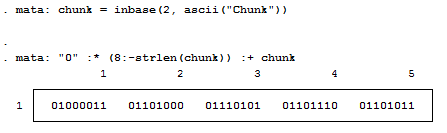

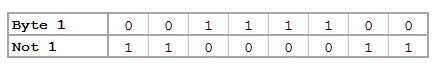

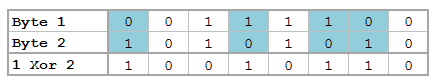

But now we want to see each bit. Remember, I'm not a computer scientist, so you can trust me when I say this really isn't all that bad for those of you who haven't been exposed to this stuff. Just know that each of these bytes contains 8 bits. Each bit can either be on or off (1 or 0) which means that there’s a total possible bit combination of 2^8 = 256 per byte. Let's look at what Stata shows us when we look at everything in base 2:

Notice, I added a zero and a one at the end of the text string "chunk" for illustrative purposes. Why are these values not 0 and 1 respectively? That’s because the digits are also ASCII characters (digits 48 and 49). We can get the values of zero and one by using the - char() - function. For fun, we'll also look at values two and three as well.

Well, because there are technically 8 bits per byte, we need to pad each output with zeros so that the total length is 8 bits. For example: the value "3" can be written as "11" in base 2, but is the same "00000011" so that we can imagine all 8 bits. We can easily accomplish this in matrix form.

Notice the use of the colon operator? It's by far one of my favorite operands (not that I have that many) because it does the same operation on each element of the matrix, which makes the overall statement extremely succinct! The statement above just says: "Give me some zeros, exactly 8 minus how every many numbers we had, and append the original statement to the end to make sure every element has exactly 8 digits."

We should probably make this into a function, since we’ll use it a lot. So let's make the size of the padding an input as well.

mata:

string matrix padbit(string matrix x, real scalar padnum)

{

string matrix y

y = "0" :* (padnum :- strlen(x)) :+ x

return (y)

}

end

mata: padbit(chunk, 8)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| bitwise-mata-functions.do | |

| File Size: | 2 kb |

| File Type: | do |

Shifts and Rotations

It's interesting to follow, though not all that interesting if it doesn't have a practical application. If you're like "honestly, I don’t know nothing about bit functions", I'll say - well I've got the one you. How about a way to easily encrypt your files so that you can hide your sensitive stuff in plain sight? First find a file and read it in:

// Read in File to Copy

fh = fopen("Building an API Library.docx", "r")

eof = _fseek(fh, 0, 1)

fseek(fh, 0, -1)

x = fread(fh, eof)

fclose(fh)

Convert the file characters to the ASCII decimal value then convert this number into the base 2 representation (don't forget to pad the bits). From here, we can use our bitwise operations before converting this number back to base 10 and finally back to characters:

// Run Bitwise Not

y = padbit(inbase(2, ascii(x)), 8)

for (i=1; i<=cols(y); i++) {

y[i] = bitnot(y[i])

}

y = char(frombase(2, y))

Lastly, write your newly altered file using Mata. This is obviously very basic, but a great way to hamper nosy coworkers.

// Write the Results to File

fh = fopen("Copy.docx", "w")

fwrite(fh, y)

fclose(fh)

But really, we're doing this with the ultimate goal of gaining access to Twitter data using Twitter's API. This is just step one of a three part series and if you're lost so far. there's plenty of time to see the motivation for this post in the next step. I promise it gets more interesting, yet I hope I've shown some of Mata's potential and how you can easily bring in the concepts to your own do-files.

For Use with Windows

A quick Google search yields many answers – most of which requires you to know a thing or two about email servers. After hours of collecting material and trying to send out emails, you'll realize that your work's firewall disallows you to do anything of the sort! Well, if you use Outlook (which is pretty common), you can easily automate sending emails using the following VBScript:

Set Outlook = CreateObject("Outlook.Application")

Set Mail = Outlook.CreateItem(0)

Mail.To = "[email protected]"

Mail.Subject = "Automated Email"

Mail.Body = "Hello Recipient"

Mail.Send

Set Mail = Nothing

Set Outlook = Nothing

But how do we send this out? It's really quite simple. Open up any text editor (though I recommend using Notepad++), copy this code into the text editor, and save this file as "whatever.vbs", and either double click the file or run it by using Stata's shell command.

yourdirectory + "whatever.vbs"

CRLF

Anyway, this combination is useful to you if you want to send multiple paragraphs in an email. Even more useful, write out your email body in a text file and let Stata pick up the file for you, and write the body by itself. But more on that in a little bit. For now, let’s talk about writing the actual script.

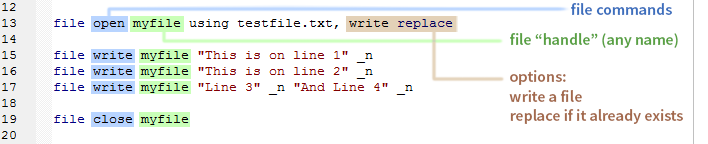

In Stata, in order to write a script, we must first familiarize ourselves with the file processing commands: file open, file write, and file close. The secret here is that we can use locals to fill out any missing information in the file such as an email recipient, a subject line, or an attachment location. Boom! We have a program.

program define outlook_email

syntax , to(string) [subject(string) body(string) attachment(string)]

end

Since we always need a recipient for an email "to" is a must, but everything else should remain optional. We want to allow our users to do whatever they want, which might include sending out 10,000 blank emails to a specific person. Why? They probably have their reasons.

File Processing

Notice that we just need to put a string followed by _n to write a single line to the file. We then do that again for line two, and for lines three and four. We're able to write lines three and four on the same line, because they contain that _n which calls for an end of line character (in this case CRLF) to be written.

The Body

- Get rid of quotes: from " to "+Chr(34)+"

- Get rid of apostrophes: from ' to "+Chr(39)+"

- Replace CRL characters: from \013d\010d to "+ Chr(13)+Chr(10)+"

- Get rid of useless stuff: from +""+ to +

Final Program

********************************************************************************

* Will Matsuoka: 2015-12-17 version 2.0.0 - for demonstrative purposes

********************************************************************************

program define outlook_email

syntax , to(string) [subject(string) body(string) attachment(string)]

* Allow for the subject to contain quotes and apostrophes

if `"`subject'"' != "" {

sta_2_vbs `"`subject'"'

local subject = r(vbstring)

}

if `"`body'"' != "" {

preserve

tempfile f1 f2

filefilter "`body'" `f1', from(`"""') to(`""+Chr(34)+""')

filefilter `f1' `f2', from(`"'"') to(`""+Chr(39)+""')

filefilter `f2' `f1', from(\013d\010d) to(`""+Chr(13)+Chr(10)+""') replace

filefilter `f1' `f2', from(`"+""+"') to("+") replace

clear

set obs 1

gen file = fileread("`f2'")

local body = file[1]

restore

}

tempname myfile

file open `myfile' using sendemail.vbs, write replace

file write `myfile' ///

`"Set Outlook = CreateObject("Outlook.Application")"' _n ///

`"Set Mail = Outlook.CreateItem(0)"' _n ///

`"Mail.To = "`to'""' _n ///

`"Mail.Subject = "`subject'""' _n ///

`"Mail.Body = "`body'""' _n

if "`attachment'" != "" {

file write `myfile' `"Mail.Attachments.Add("`attachment'")"' _n

}

file write `myfile' ///

`"Mail.Send"' _n ///

`"Set Mail = Nothing"' _n ///

`"Set Outlook = Nothing"' _n

file close `myfile'

shell sendemail.vbs

end

program define sta_2_vbs, rclass

local string = subinstr(`"`1'"', `"""', `""+Chr(34)+""', .)

local string = subinstr(`"`string'"', `"'"', `""+Chr(39)+""', .)

local string = subinstr(`"`string'"', `"+""+"', "+", .)

return local vbstring `"`string'"'

end

Not too terrible, although I do have a few things to note:

- For troubleshooting, if your VBScript works, your Stata script should work - in other words, start at your VBScript

- There are times where it helps to keep Outlook open, to make sure that your email doesn't just sit in the outbox

- If you're trying to run this in batch mode, omit the shell command. Just call the script on the next line of your batch file (since shell doesn't work in batch mode)

On writing binary files in Stata/Mata

We start by making up a fake type of file called a wmm file. This file always begins with the hex representation ff00, which we know just means 255-0 in decimal or 11111111 00000000 in binary. The next 20 characters spell out “Will M Matsuoka File” followed by a single byte containing the byte order or 00000001 in binary. From there, the next four bytes contains the location of our data as we put a huge buffer of zeros before any meaningful data. It makes sense to skip all of these zeros if we know we don’t need to ever use them. After these zeros, we’ll store the value of pi and end the files with ffff.

The file looks like this:

Stata's File Command

tempname fh

file open `fh' using testfile.wmm, replace write binary

file write `fh' %1bu (255) %1bu (0)

file write `fh' %20s "Will M Matsuoka File"

file set `fh' byteorder 1

file write `fh' %1bu (1)

* offset 200

file write `fh' %4bu (200)

forvalues i = 1/200 {

file write `fh' %1bs (0)

}

file write `fh' %8z (c(pi))

file write `fh' %2bu (255) %2bu (255)

file close `fh'

The only thing I feel I need to note here is the binary option under file open. Other than that, take note that we’re setting the byteorder to 1. This is a good solution to writing binary files; however, since most of my functions are in Mata, we might as well figure out how to do this in Mata as well.

Mata's File Command

mata:

fh = fopen("testfile-fwrite.wmm", "w")

fwrite(fh, char((255, 0)))

fwrite(fh, "Will M Matsuoka File")

// We know that the byte order must be 1

fwrite(fh, char(1))

fwrite(fh, char(0)+char(0)+char(0)+char(200))

fwrite(fh, char(0)*200)

fwrite(fh, char(64) + char(9) + char(33) + char(251) +

char(84) + char(68) + char(45) + char(24))

fwrite(fh, char((0,255))*2)

fclose(fh)

end

I personally like the aesthetic of this syntax; it’s clean, neat, and relatively simple. The only problem is its ability to handle bytes. In short, it doesn’t do it at all. We’d have to build some more functions in order to accomplish this task (especially when it comes to storing double floating points) which is why Mata also has a full suite of buffered I/O commands. It’s a little more complicated, but well worth it. After all, we cheated in converting pi to a double floating storage point by using what we wrote in the previous command. This is not a good practice.

Mata's Buffered I/O Command

mata:

fh = fopen("testfile3-bufio.wmm", "w")

C = bufio()

bufbyteorder(C, 1)

fbufput(C, fh, "%1bu", (255, 0))

fbufput(C, fh, "%20s", "Will M Matsuoka File")

// We know that the byte order must be 1

fbufput(C, fh, "%1bu", bufbyteorder(C))

fbufput(C, fh, "%4bu", 200)

fbufput(C, fh, "%1bu", J(1, 200, 0))

fbufput(C, fh, "%8z", pi())

fbufput(C, fh, "%2bu", (255, 255))

fclose(fh)

end

The one distinction here is the use of the bufio() function. It creates a column vector containing the information of the byte order and Stata’s version, but allows us to use a range of binary formats available to use in Stata’s file write commands.

Reading the Files Back

mata:

void read_wmm(string scalar filename)

{

fh = fopen(filename, "r")

C = bufio()

fbufget(C, fh, "%1bu", 2)

if (fbufget(C, fh, "%20s")!="Will M Matsuoka File") {

errprintf("Not a proper wmm file")

fclose(fh)

exit(610)

}

bufbyteorder(C, fbufget(C, fh, "%1bu"))

offset = fbufget(C, fh, "%4bu")

fseek(fh, offset, 0)

fbufget(C, fh, "%8z")

fclose(fh)

}

read_wmm("testfile-fwrite.wmm")

read_wmm("testfile.wmm")

read_wmm("testfile3-bufio.wmm")

end

And there you have it, a bunch of different ways to do the same thing. While I enjoy using Mata’s file handling commands for its simplicity, it does get a little cumbersome when writing integers longer than 1 byte at a time. Time to start making your own secret file formats and mining data from others.

Author

Will Matsuoka is the creator of W=M/Stata - he likes creativity and simplicity, taking pictures of food, competition, and anything that can be analyzed.

For more information about this site, check out the teaser above!

Archives

July 2016

June 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

Categories

All

3ds Max

Adobe

API

Base16

Base2

Base64

Binary

Bitmap

Color

Crawldir

Email

Encryption

Excel

Exif

File

Fileread

Filewrite

Fitbit

Formulas

Gcmap

GIMP

GIS

Google

History

JavaScript

Location

Maps

Mata

Music

NFL

Numtobase26

Parsing

Pictures

Plugins

Privacy

Putexcel

Summary

Taylor Swift

Twitter

Vbscript

Work

Xlsx

XML

RSS Feed

RSS Feed