Why Care Block:

Yo yo, what’s up my Stata-ites! DJ Control+D is in the house because today we’re talking about making music with Stata. There’s a big trend in today’s age involving visualizations, but truth be told, visualizations are so last season. You’ve always been able to see your data, yet have you ever wanted to hear your data? “That’s absurd, I don’t need that.”

Yeah, you’re probably right... but today, this post is for the slacker: from the undergraduate struggling through their Stata homework, to the professional who’s bored with the day-to-day grind, our new command composer is there to brighten up your day and aid with your ever evolving procrastination techniques. What is composer? It’s a way to create music. How is that music generated? You write a string of notes that get converted to the midi file format. Why did we do this? I’m still asking myself that same question while introspectively reevaluating my life. Truth be told, I love music. Not in the traditional sense, but in the very traditional sense – classical music and music theory has always been a passion of mine and this has been a passion project for a long time now. Composer makes music in two separate ways. You can write songs from the command line and from a dataset. The command line approach is faster and is especially meant for ad hoc procrastination. The dataset approach is a more methodical way of creating music and actually allows for multiple tracks and multiple instruments. Take our command line approach: composer "D, 384D, A, A, B, B, *2A, G, G, F#, F#, E, E, *.25r, *.25Db, 768D" using tt.mid, play replace We could have also written this first part as D, D, A, A, B, B, 768A, but it’s good to see the variations of this command. First we have notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Each note can be modified using a # (sharp) or a b (flat) which directly follows the note. A number before the note shows the duration of the note. The quarter note takes the value 384 (3*2^7). This way it can be halved up to seven times with 384 representing a quarter note, 192 representing an eight note, 96 a sixteenth note, and so on. Rather than specify a value, you may also multiply the note by a number to modify the value of the quarter note. Any number following your note denotes which octave or pitch your note will take. You may also change the instrument using a number or a named instrument available in the composer help file. For instance, say we wrote:

local n1 = "F#,A,E6,D6,E6,D6,A,D6"

local n2 = "E,A,E6,D6,E6,D6,A,D6"

local n3 = "F#,B,E6,D6,E6,D6,B,D6"

local n4 = "G,A,E6,D6,E6,D6,A,D6"

composer "`n1',`n1',`n2',`n2',`n3',`n3',`n4',`n4'" using ls.mid, play replace instrument("Pizzicato") bpm(240)

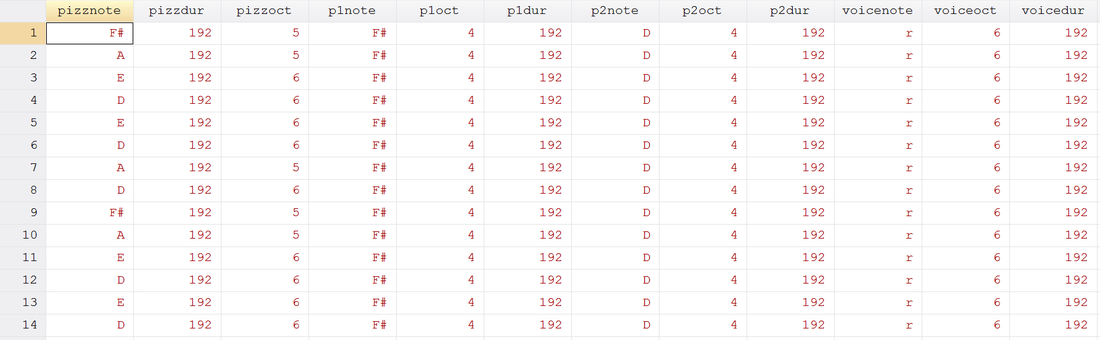

See if you can identify the song! Now take our data set approach. It’s just like the command line approach, except the command now takes sets of three variables: time duration, note, and octave. Notes can be played simultaneously by adding another track (three more variables). This way we can build chords and add volume to our masterpieces just like Beethoven. But unlike Beethoven, we’re not creating classical masterpieces, we’re recreating pop music. If you weren’t able to pinpoint the song before, here’s the dataset aided version of our previous track.

use http://www.wmatsuoka.com/uploads/2/1/4/6/21469478/ls.dta, clear composer pizzdur pizznote pizzoct p1dur p1note p1oct p2dur p2note p2oct voicedur voicenote voiceoct using ls.mid, play replace bpm(120) instrument(Pizzicato Pizzicato Pizzicato Voice) And there we have it, a fairly easy way to write music in Stata. Is this interesting? I hope so, especially if you’ve made it this far. I’m sure you’re wondering how useful this is though. Truth be told, this is probably one of the only things on this blog that I haven’t found a general use for but perhaps you can find some sort of practical application and share your thoughts. There will be one more post about music soon which deals with the actual analysis of music which will use composer. Until then, good luck and stay creative future Stata maestros!

25 Comments

I was extremely lucky to receive an advanced copy of gcmap written by the folks over at www.belenchavez.com. You see, gcmap is an excellent program that uses Google Charts API to create professional web quality charts using your Stata datasets. Don’t believe me? Check out this example below.

Every NFL team, every NFL stadium, with pictures! This dataset was created by using information from Wikipedia. I’ve taken my fair share of stuff from Wikipedia, but I’ve also donated every year to the Wikimedia foundation, and you should too!

Today is December 13, 2015 – which also marks Taylor Swift’s 26th birthday. Happy Birthday, Taylor! In an extension to NFL stadiums, I’ve merged data from all the North American locations Taylor Swift played at in her 1989 World Tour. Here’s another example of how you can use gcmap in order to produce some great (although somewhat creepy) maps.

Enjoy - I hope we see a lot more Stata + Google Charts in the months to come!

Next up: NFL Injuries – an Artistic Approach

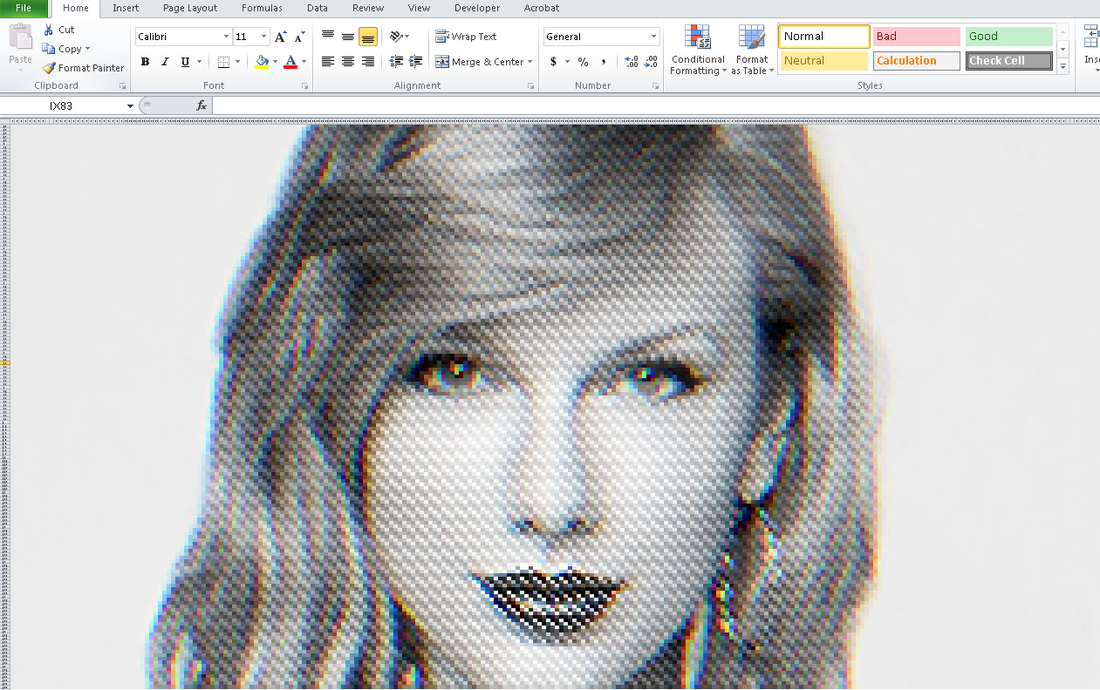

Check it: Excel Art.

Stata 14 – a cause for fanfare – expanded Stata’s abilities to format excel files. Sounds exciting right? You’re damn right. Excel files no longer have to be pre-templated before the dreaded export excel messes up your number formatting. Putexcel used to alleviate this problem in Stata 13, but only for numeric matrices. Luckily for us those days are long lived but long gone, and putexcel evolved into a very useful command.

So what’s the first step in creating this captivating art? Finding an easily parsable file format of course. The EPS (Encapsulated PostScript) format does just that – take a look for yourself: EBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEAEAEAEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEB EAEAEBEBEBEBEAEAEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEAEAEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEB EAE4E7E5E3DECFB292948D97A29D9F9D9FA9A6A49477726A5D4F484A4742484B 453B36302E2C302E2F3735332C2B32322C2D393C423E3738404950575E5F605B 545D655D5E5C5E6C6972767D888D9DA9B4B9BAC1B7ADA19995907A66646E6C7C 9099B7A99F9E9CADAB97838FB1CDE1E9ECEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEB EBEBEAEAEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEBEB EAEAEBEBEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEAEBEBEBEBEBEBThere’s no binary, just text. And while it may look like the transcript of a sugared-out toddler, it contains a lot of good color information. The first thing to know is that all colors we deal with are related to light. The three additive primary colors are red, green, and blue. If you ever looked closely at an old TV screen (like I did as a young’un), you’d see these three distinct colors. In this case, each color uses 8 bits: 2*2*2*2*2*2*2*2 = 256 possible combinations per color. Each color then gets a number from 0-255. Zero means the color is off while 255 corresponds with a full-on color! So RED in RGB mode would look like this: “255 0 0”. Converting this number to base 16 yields “FF 00 00” or “FF0000” without spaces. Going backwards: “EAE4E7” is the same as “EA E4 E7” which converts to “234 228 231” in base 10. This is made easy with Mata’s frombase command. After a few tricks - such as finding the right order of the data stored - we’re able to convert the previous gibberish to pixel information/excel cell information. This is where putexcel gets good. The matrix of color information is passed to a Stata dataset so that it utilizes the fpattern cell expression of putexcel. An example Stata variable would look like this: V1 A1=fpattern(“solid”, “234 243 243”) A2=fpattern(“solid”, “234 243 243”) A3=fpattern(“solid”, “234 243 243”) Because we have a column of strings we can use the levelsof command to create a list containing each of these expressions and write them directly using the putexcel command. Now we’re ready to shake shake shake out that final command:

foreach v of varlist * {

levelsof(`v'), local(`v') clean

local cellexp = "`v' `cellexp'"

}

local cellexp = subinstr("`cellexp'", " ", "' ", .)

local cellexp = subinstr("`cellexp'", "v", "`v", .)

putexcel `cellexp' using "Art.xlsx", sheet("LoveStory") replace

The trick here is using the option "clean" in our levelsof command to strip all the double quotes so that we can use it directly in our putexcel statement. While we could have included the putexcel statement within the loop, the advantage here is that, because we’re only calling the command once, we don’t have to continually open and close the excel file for each putexcel statement - making it run in seconds. Now we’re ready to find our Starbucks lovers, get in fights at 2:30 am, and never ever get back together because we just saved ourselves so much time! Can you spot all the Taylor Swift references? I count seven. |

AuthorWill Matsuoka is the creator of W=M/Stata - he likes creativity and simplicity, taking pictures of food, competition, and anything that can be analyzed. Archives

July 2016

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed